Injury at Birth: What Went Right, What Went Wrong

If you are a mother whose baby suffered from a birth injury, you may want to skip this story.

New parents are often worried about the shape of their newborn baby’s head. Molding of the skull bones occurs commonly during delivery and can make the baby’s skull misshapen in many different way. (A newborn’s skull bones are unfused and quite malleable.) A newborn’s bruised and swollen scalp is called caput succedaneum. It is also of concern to many new parents, but these things are benign, that is - they are not birth injury. A caput results from pressure on the presenting part.

No new parent wants to be informed of a true birth injury in their newborn baby. Thank goodness, birth injuries are rare these days. The overall incidence of birth injuries in the U.S. is 1.9 per 1,000 live births (CDC and AHRQ data).

Rates of birth injury have decreased significantly over the last few decades due to improved obstetric practices and increased use of cesarean section (when indicated).

There are many reasons for prenatal care, and identification of risk factors for birth injury is one of them. These include maternal diabetes and macrosomia (a large baby over 4 kg or 8 pounds 13 oz.).

Similarly, there are many reasons for your delivery to be attended by a well-trained and experienced obstetrician or nurse midwife, preferably in a hospital or birthing center. Certain conditions during labor and delivery increase the risk of birth injury in your newborn and you need someone there who is trained to manage them. These include prolonged labor, instrumented vaginal delivery (vacuum/forceps), and shoulder dystocia.

During my practice I encountered many newborns with birth injuries and was required to explain what happened to the new, worried parents. That was never an easy task, although usually outcomes were good.

The most common birth injury is cephalohematoma, which occurs in about 1% to 2% of all live births. These are more common in instrument-assisted deliveries (e.g., using forceps or vacuum).

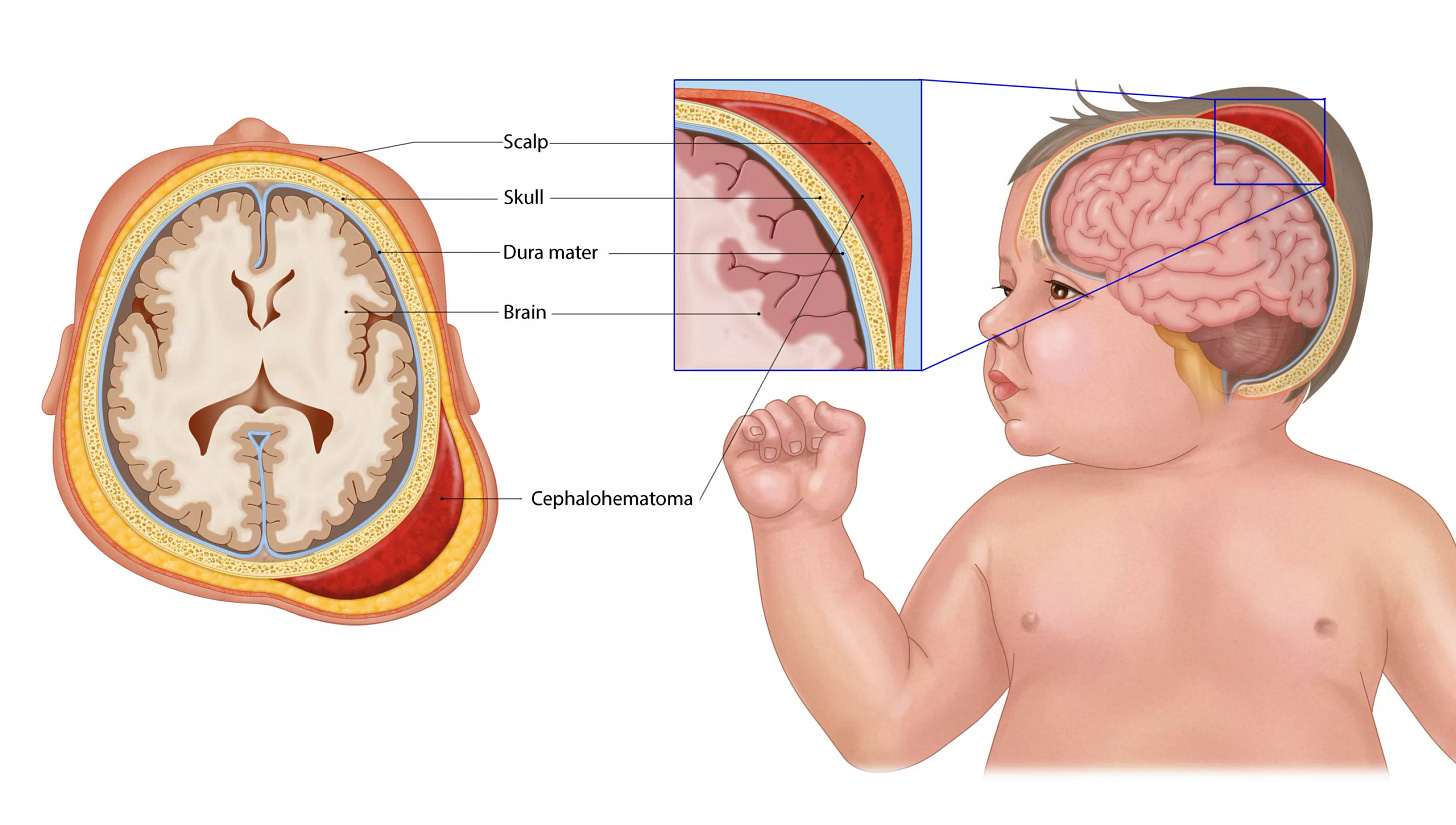

A cephalohematoma is a blood collection between the skull and periosteum, typically limited to one cranial bone. Ultrasound or X‑ray may be used to confirm if there’s a skull fracture. Fortunately, cephalohematomas are usually benign and self-resolving, but large hematomas may contribute to jaundice or anemia.

Many of you may remember your pediatrician telling you about this large, boggy bump in your newborn’s scalp. And you watched it resolve over days to weeks.

I have seen several skull fractures over the years, also associated primarily with instrumented delivery. Sometimes skull fractures occur spontaneously after delivery of macrosomic infants (very large infants) born to diabetic mothers. Skull fractures are rare, occurring in 2.9 per 10,000 live births.

Most skull fractures are linear and heal without intervention, but depressed fractures may need surgical evaluation. I have a story to illustrate this kind of skull fracture. These new parents were certainly taken aback, worried, and fearful, but all ended well for their baby.

Early in my career, one birth injury case at Texas Children’s Hospital, in Houston, impressed me greatly. This was a newborn with a depressed skull fracture. He was born by forceps-assisted vaginal delivery by a well-trained and talented obstetrician. Talking with the obstetrician, labor nurse, and the parents reassured me that the stainless-steel forceps blades had been placed properly around the baby’s head and used correctly to gently guide his delivery. No torsion was exerted, and no unnecessary pulling was described. Soon after birth, however, the baby had a brief seizure that prompted his admittance to the NICU.

There was a peculiar spot at the side of his head on the left where his skull was dented - like a ping-pong ball. His neurological exam was normal, but a CT scan of his head revealed the depressed skull fracture and a grape-sized epidural hematoma. This is a hemorrhage, or blood clot, that lies underneath the skull bone and presses on top of the brain. The hematoma required surgical evacuation, and the depressed fracture needed to be lifted.

After undergoing neurosurgery that day, the baby returned to the NICU very stable. His coagulation (clotting) studies proved to be normal, and he recovered nicely. The parents were told that this was “just one of those things—sometimes complications happen.” This is actually true: sometimes a procedure can be done with perfect technique and still something untoward will happen.

This obstetrician knew these parents well and, as a result, they coped nicely with this unexpected occurrence in their son. Of course, they were extremely worried when he had the seizure and needed NICU care, but when the CT scan defined the cause, and the neurosurgeon was there to intervene, they felt some refief. As their son stabilized post-op, woke up, fed well, and acted like a normal newborn they settled into the routine of typical delighted new parents. They all went home three days later, and fortunately, this baby recovered fully.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Moms Matter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.